Publisher/Date:

Multi-Man Publishing (2022)

Product Type:

HASL/Historical Module

Country of Origin:

United States

Contents:

6 24" x 37" historical maps on semi-gloss paper; 24" x 23" reduced-size combined historical map on semi-gloss paper; 4 sheets of die-cut counters (with 700 1/2" counters and 264 5/8" counters, for a total of 964 counters); 25 scenarios on cardstock (SF1-SF25), 40 pages rules (Chapter SF, pages SF1-SF40), 3 chapter dividers w/charts & tables.

Sword and Flame: Manila, a historical module released by MMP in 2022 that depicts the month-long battle between the U.S. and Japanese for the city of Manila in February 1945, is an ASL product with an almost famously long gestation time–over 20 years. It’s not clear exactly when primary designer Dave Roth started research for his Manila project, but a comment about the prospective module can be found in a gaming forum as early as 1999. A crude playtest kit was available by late 2001, and Your Humble Author was one of the earliest playtesters. This original version of Manila had maps hand-drawn with color pencils. The buildings did not conform to the hexgrid but jutted out significantly all over the place (this was later corrected in a new version of the maps). At that time, the rules for Manila had each floor of a building corresponding to a separate Level, with the result that there were buildings on the map that were six or more Levels in height (which made for interesting stacks). The initial playtest version already contained a large number of scenarios (24; plus 5 campaign games), which offered players the relatively rare experience of really sinking their teeth into city-fighting with or against the Japanese. Your Humble Author playtested multiple scenarios, including at Winter Offensive 2002, and his young heart thrilled the first time his HIP Japanese squad with a flamethrower made quick work of an attacking American platoon. It was also fascinating just to explore the city, from the Intramuros, the thick-walled old fort, to the Pasig River.

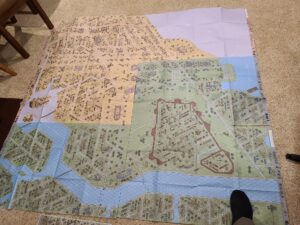

Printer proofs of Manila maps during production process. Credit: MMP.

Work on Manila continued long after Your Humble Author’s involvement ended. Every now and then a revised version of the map would appear, allowing one to see the improvements and developments. Finally, the project was submitted to MMP. It was not initially clear if they would be interested in publishing the entire module, or might want to publish it in two parts, like Kampfgruppe Peiper, or would only publish a partial version. No one had ever published an ASL project with such a large map area before. Unfortunately, the module was submitted in the mid-2000s, aka The Doldrums, a period when MMP released new products at an agonizingly slow rate. Moreover, Manila did not seem to have an internal “champion” at MMP, which is often needed for a product to be put on the front burner. Finally, Code of Bushido, the ASL PTO module, was long out of print and its replacement was still far off. Those factors, combined with Manila’s large size and non-ETO nature, led to what one might call “a lot of little action.” In 2007, an MMP principal simply said, “We are not putting out the Manila HASL just now.” In 2010, playtesting was going on but there was as of yet no attempt to put it on MMP’s notional publishing schedule. In 2014, MMP employee Chas Argent stated on Consimworld that the Manila HASL still needed a great deal of work and development. At least it was clear that work was being done on the module. Still, it was not until early 2021 that MMP finally put the module up for pre-order. Sword and Flame: Manila finally came out the following year, more than two decades after its journey began.

In the end, MMP decided to print Sword and Flame: Manila (hereinafter SFM) as one large module. Back in the 2000s, ASLers debated whether or not they would even consider buying SFM if it cost more than $100. As of this writing, MMP is selling SFM direct for $132.00. That is expensive, yes, but still less expensive than Festung Budapest ($194.00) or Red Factories ($164), despite containing more maps and more scenarios (although fewer new counters). Considering the contents as well as the large amount of play value, the price is actually fairly reasonable.

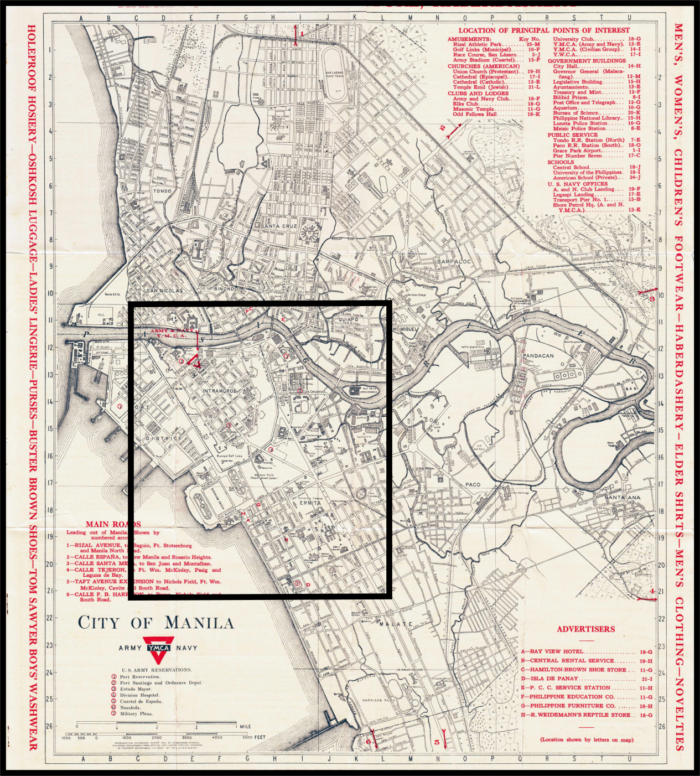

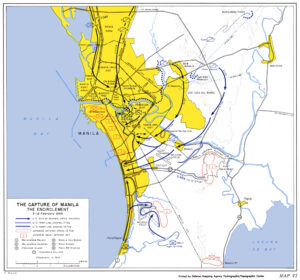

SFM does not depict the entire battle of Manila, nor does the map depict the entire city (which was quite large and spread out). Missing from the battle are the 37th Infantry Division actions in the north of the city early in the battle, as well as all of the fighting of the 11th Airborne Division, which fought on the southern outskirts and districts of Manila. The fighting concentrates on the actions of the 37th Infantry Division and 1st Cavalry Division attacking the core

Intramuros area after the battle.

Japanese defenses south of the Pasig River, including the Japanese attempt to hold the walled city of Intramuros. The map area depicted in SFM consists largely of the Intramuros and Ermita districts and their surrounding terrain (Manila regions have had different names at different times). As with any ASL HASL map, the SFM map is considerably stylized so that the terrain can fit the hex grid and not cause other ASL rules issues. In so doing, the map does not always capture the building density in some areas, such as Intramuros. Unlike the Budapest of Festung Budapest, which provides a more or less pristine city that is “destroyed” during play or through laborious processes prior to the start of individual scenarios, the Manila of SFM, like the Stalingrad of Red Factories, comes pretty pre-destroyed, with plenty of rubble (of three kinds), debris, and shellholes. By the time the battle was over, Manila would sadly become one of the most completely destroyed cities in World War II.

The SFM map comes in six sections that fit together in a 3×2 grid; because of the contours of the coastline, one of the maps is mostly water. The complete map is an impressive and very large array, too large for the average gaming table, so the largest campaign game will likely be out of the reach of most players. The maps are printed on fairly thin semi-gloss paper with lots of folds (the folds divide each map into 12 sections, for 72 total fold-sections). Desperation Morale remains somewhat concerned about the durability and strength of the paper MMP has been using for its historical maps in recent years, and would still prefer a thicker stock (and fewer folds). Of considerable importance is that the hexes on these maps are only 13/16″ in size, rather than the 1″ size of Red Factories maps, which means they are roughly equivalent to geoboard hex sizes (geo = .8″; SFM = .8125″). Considering the dense urban settings and many multi-hex buildings, counter congestion is certainly possible here.

Swimming pool a little worse for wear. Credit: BraveDave.

Generally speaking, the SFM maps are attractive and contain a lot of historical detail, including the name and function of many buildings, street names, and other features. The terrain is interesting, with many long avenues and large areas of open terrain, as well as more congested areas and more destroyed areas. Depending on what part of the city the fighting takes place in, the feel can be quite different. The winding Pasig River also has an important impact on the terrain, as do the walls of the Intramuros. Overall, the terrain is very flat, but the large buildings, which can be up to 3.5 levels tall, certainly can play a big role (note that the 1 floor = 1 level original standard was thankfully dropped in favor of a more abstract but far, far more playable rules depiction).

An important feature of SFM and its maps is the variety of building terrain; this is also a bit of a shortcoming, as far as the maps are concerned. SFM is full of buildings of a variety of kinds, including standard stone and wood buildings, but also including Adobe Buildings (which are mostly like stone buildings), Multi-Material Buildings (which have a stone or adobe ground level and wood upper levels), Steel-Walled Buildings (which have a +5 TEM!), Warehouses (a factory variant), and Open Air Workshops (which have no building walls and hinder rather than block LOS).

That’s a lot and they are not all that well distinguished from each other on the SFM maps. Perhaps the biggest problem is that wooden buildings have only a faint brown color, which makes them sometimes hard to distinguish from stone buildings (complicated even more by the fact that stone buildings themselves do not have a uniform hue–some are lighter and some are darker). The adobe buildings actually seem more brown than wooden buildings. It would have been better to distinguish more clearly between stone and wooden buildings, and then to make adobe buildings redder still. The different types of rubble–stone, wood, and adobe–could also have been more clearly distinguished. Steel-walled buildings, meanwhile, are represented by “blue-colored buildings” with a “small white hex center dot surrounded by a thin white box.” However, on the map the buildings don’t look “blue” at all but are just slightly darker than stone buildings. Were it not for the center dot in the white box, these buildings would be very hard to distinguish. Multi-Material Buildings are also frustrating, they are distinguished from other types of building by having a “thin gray stone outline” that surrounds a “brown wooden” interior. Unfortunately, because the wood building color is not well-distinguished from the stone building color, one has to look closely to determine which buildings are Multi-Material buildings. To make it even more difficult, there are some stone buildings that themselves have a thin stone outline around them.

All of this frustrating and makes extra efforts for players, especially if they are playing in less-than-optimal lighting conditions. It would have been so easy to more clearly visually distinguish between the different types of buildings; it’s disappointing that MMP did not do so. Ironically, MMP missed an additional way to help players. Because there are so many buildings, MMP actually devotes several rules page to a long chart that lists buildings and gives the number of stories that they historically had and their topmost level in ASL terms. The list for some reason only includes named buildings, however, rather than all multi-hex buildings, and organizes them in alphabetical order by name rather than by map and hex. It would have been better to have a list of all multi-hex building, organized by map and hex number rather than by name, and including the type of building and other pertinent info (such as whether or not it is a factory). Then players unsure about a building could easily double-check its status. However, this was not done.

It’s worth noting that the large map area creates problems in terms of hex numbering. MMP decided to have one huge numbered hexgrid, rather than separately-numbered hexgrids for each map. In the rules, they identify hexes only by hex number rather than by map and hex number, so players looking for a specific hex may have to fumble through their maps to find it. Moreover, when the hex grid passes the Z hexrow, it does not go to AA but rather to 2. So a reference to hex 3K40 does not refer to hex K40 on map 3 (which would be easy to find) but rather to (what would be, in standard ASL terms) hex KKK40 on one or another of the maps. This takes getting used to.

MMP provides both black and white and color miniature maps of the map area portrayed in SFM, for use with campaign games, but also uniquely provides a larger 24″ x 23″ reduced-sized historical map showing the entire playing area. It’s not 100% clear what purpose this map is for.

MMP provides both black and white and color miniature maps of the map area portrayed in SFM, for use with campaign games, but also uniquely provides a larger 24″ x 23″ reduced-sized historical map showing the entire playing area. It’s not 100% clear what purpose this map is for.

SFM comes with 40 pages of rules, although this includes the list of buildings, some historical background, and other items. Players not playing a campaign game will have to master about 6 pages of rules. The campaign game rules contain no real surprises and should be familiar to anyone who’s played an official campaign game before.

Other rules provide for generous Japanese sewer movement (which represents more than just sewers), American hand-to-hand combat (scary for the Japanese), Japanese using DCs during Close Combat, lots of rules for the Intramuros walls and narrow roads, and various unique terrain types (the Coal Pile, Cattle Pens, etc.). Overall, the rules for SFM are not complex (certainly less complex than Festung Budapest) and players can jump in fairly easily (unless playing a scenario involving the Intramuros walls, which take a little absorbing). SFM has chalked up a small amount of errata since its release, which should be noted. MMP has SFM errata here, but this version of the errata contains some additional scenario errata that is for some reason not on the MMP website (as of this writing, anyway).

There’s one rule missing from SFM that should be there. During the battle for Manila, the Americans developed a highly effective tactic of entering buildings from its rooftop (typically having gotten to the rooftop via the rooftop of an adjacent building), then fighting their way down, clearing floors as they went. However, although rooftops are in play in SFM, the module does not provide the rules to allow this (despite the fact that this tactic is even explicitly mentioned in a footnote!). What is needed are rules to allow U.S. units to cross from a rooftop to the rooftop of an adjacent building at the same level (and perhaps also to up to one level lower), as well as a rule that would exempt such units from upper-level encirclement as llong as they had access to a rooftop. The SFM rules do treat U.S. assault engineers as Commandos, which allows them to use Scaling (so they could climb to rooftops via the outside of buildings), but they do not allow building-to-building rooftop movement.

SFM comes with four countersheets, most of which are duplicates/extras for use with large scenarios and campaign games. Sheet 1, a sheet of half-inch counters, mostly provides American infantry and accoutrements, including new 7-4-7 assault engineer squads and half-squads. Sheet 2, also a sheet of half-inchers, provides Japanese infantry and SW. New counters include 4-4-8 assault engineer squads and half-squads, as well as 8 (captured) U.S. machine-guns in Japanese colors. Sheet 3 is a sheet of 5/8″ counters, half of which are markers of various kinds–location control, blaze, berserk, and so forth. Most of the remaining counters are additional US AFVs and guns.

The fourth countersheet contains a variety of 5/8″ markers, especially rubble, as well as a bevy of Japanese guns. New counters include 10 “Bomb Crater” counters to place when buried Japanese bombs explode. Yikes.

Stuck in among all the SFM counters are a few counters not intended for this product, including 2 1/2″ and 8 5/8″ “British 3-inch MTR alternatives.” There did not seem to be a written explanation for these counters, but the buzz in the ASL world for some time has been that the British 3-inch MTR was actually equivalent to an 81mm MTR rather than a 76mm MTR as portrayed in the ASL British OB. Apparently, these counters are for ASLers who want to play it that way.

There are also 10 counters–flamethrowing tanks and armored bulldozers–that are intended to be replacement counters for Forgotten War counters with errata. SFM players will be sad to learn those nasty flamethrowing tanks aren’t toys for them to play with.

One note of caution: the counters in SFM are fairly deeply die-cut and can thus easily come off their counter trees. So be careful with the countersheets until you are ready to punch the counters and add them to your Preferred Storage Method™.

SFM comes with five Campaign Games. CGI (Clearing the North Shore) is a 6-date campaign game featuring the 37th Infantry Division’s clearing of the north shore of the Pasig River. It takes place on Maps 1 and 2 but only on the area north of the Pasig River–which is a very long and narrow area, perhaps the strangest area for any ASL campaign game. CGII (Fighting for he Fortresses) is a 10-date campaign game that uses most of Maps 1-4. It features the 37th Infantry Division’s attack on the Japanese fortified positions south of the Pasig.

CGIII (1st Cavalry Moves North) has 12 campaign dates divided into two phases, each with its own map configuration (Phase One uses parts of maps 5 and 6; Phase Two uses maps 3 and 5, except for Intramuros). It depicts the entry of the 1st Cavalry Division on the scene after it outflanked Manila to the east and entered the city from the east and southeast. CGIV (The Walled City), as its name suggests, features the battle for the Intramuros. It has 7 campaign dates and only uses the area around the old fortress on Maps 1 and 3. In this sense, CGIV is probably the easiest campaign game to get into, because it uses the smallest map area. CGV (Destruction of the Pearl) is the largest campaign game, using 15 campaign dates to depict the period from February 15 to March 1, when the fighting was at its most furious. It uses the entire Manila map. It’s a very large campaign game.

Both sides have good reinforcement purchase options, especially the Americans, who can purchase a variety of assets to fight on land and sea (but no Air Support, as MacArthur had prohibited bombing the city). The Japanese have fewer choices (primarily because of a lack of AFVs, although the Japanese can purchase bicycles), but they can buy a variety of Guns, as well as some interesting OBA (including 450mm Rocket OBA).

SFM also comes with 25 scenarios, an unusually large number of scenarios for a HASL, and a good thing, because they can llet players dig into the fighting for Manila without having to find a gynormous table to play it on. The scenarios take place in a variety of areas of the map but have some similarities. Most of them are long to very-long scenarios that will take time to play. Moreover, the Americans are the attacker in virtually every scenario. This is in large part due to the nature of the situation. Unlike many other famous “city fights” (Stalingrad, Warsaw 1944, Budapest, etc.), where there were plenty of attacks and counter-attacks, especially on the tactical level, the Japanese defenders of Manila were unusually passive–primarily because most of them were not trained infantry. They were naval personnel given weapons and dropped into fortified buildings. Tactical maneuvers were beyond the abilities of most of them. Accordingly, in SFM, the Japanese are almost always the defender, hunkered down while trying to deal with American assaults. This can transmit a sort of sameness to a lot of the scenario situations, though there’s not too much the designer could have done about it–it’s just in the nature of this battle.

Most of the scenarios in SFM are large or very large in size (16 of 25). Five more are medium-sized, while four are small. Air Support appears in no scenarios and Night rules in only one, but OBA is featured in 9 scenarios. In many scenarios, the participants are definitely loaded for bear, having so many support weapons they are probably dropping parts as they move. In SF1 (Race to the River), for example, 24 U.S. squads share 19 support weapons, while 24 Japanese squads and crews have 19 SW of their own. In SF5 (No Safe Refuge), 27 U.S. squads have 23 SW, while their Japanese opponents (21 squads and crews) have 13 SW. In SF9 (First, Do No Harm), the 20.5 American squads have 16 SW and the 25 Japanese squads and crews have 15 SW. Other scenarios are similar. There’s a lot of firepower in these scenarios. There are also a lot of flames. The U.S. player almost invariably has one or more flamethrowers, while the Japanese have a flamethrower in a lot of scenarios as well. In many scenarios, the U.S. player may have a flame-throwing tank as well (often secretly designated!).

SSRs aren’t too many and are pretty straightforward. “Color” SSRs helping to give a little flavor to the action of scenarios are pretty rare. Victory conditions vary but strongly concentrate on building control or occupation, with various permutations. Some scenarios give a CVP cap to the U.S. player.

Scenarios range in geographic area from using an entire map all the way down to tiny portions of a map. A little irritatingly, a lot of scenarios take place in areas where two maps join, thus requiring the use of both maps. More scenarios take place on smaller map areas than larger areas, but there is a fair amount of variety. Of the 25 scenarios, 11 take place on the juncture of two maps (the combos vary), while 3 take place just on Map 1, 1 takes place just on Map 2, 2 occur just on Map 3, 2 more occur on Map 4, none use Map 5, and a full 6 use Map 6.

Two scenarios are rather different from the others because of their amphibious element. SF2 (Power Struggle on Provisor) features a U.S. assault boat on the islet of Provisor in the Pasig River (where a coal-generated power plant was located). On a larger scale, SF17 (Assault Across the Pasig) features the U.S. assault crossing to the south shore of the Pasig River. The scenario is 11.5 turns long and uses all of Map 1. The 24 American squads (with lots of toys, including 4 flamethrowers) get LVTs and assault boats to get them to the far shore, where the Japanese have 18 squads and 7 guns, among other things, waiting in store for them.

Overall, Sword and Fire: Manila is a good product, offering above all a lot of straight-forward city fighting with the twist of having Japanese participants. The large playing area allows a lot of different terrain configurations, while the 5 campaign games and 25 scenarios give players a lot of opportunities to explore them. The main drawback is the nature of the historical context: the Japanese defend in almost all the scenarios and are operationally on the defense in all of the campaign games. That’s something that can’t really be avoided while at the same time remaining true to the history of the subject at hand. What could have been avoided, though, are the building types that probably should be more visually distinguishable from each other. These drawbacks, however, do not outweigh the positives that this product has to offer.

Leave A Reply