Publisher/Date:

Multi-Man Publishing (2018)

Product Type:

Non-WWII (Official) Expansion Module

Country of Origin:

U.S.A.

Contents:

4 8" x 22" unmounted geoboards (80, 81, 82, 83), 7 die-cut countersheets with 242 5/8" counters and 1,480 1/2" counters, 16 scenarios (203-218), 54 pages rules (including 18 pages of Chapter W rules and 36 pages of Chapter H rules), Chapter Divider/charts

Forgotten War Commentary Table of Contents

Introduction

Welcome to Korea. Americans fought both a war and a sitcom there. You may not remember the war; according to MMP, Korea was “the forgotten war.” MMP is very sure of this; it even gave the name “Forgotten War” to two separate wargames about Korea. But it happened. Trust us.

Forgotten War: Korea: 1950-1953 is the first official ASL venture outside of the combined World War II/Sino-Japanese War, except for a few scattered scenarios. Here MMP dedicates an entire module to representing the Korean War ostensibly as accurately, as completely, and in as much detail as World War II. Thus this is not a run-of-the-mill offering but a very special product, which is why this write-up is so long that we gave it its own Table of Contents, so that you can, if you desire, skip the history of the module or even skip all of the detailed description and grousing and get right to the bottom line. Or you can read the whole darn thing, like a true American would, by jiminy.

ASLers interested in Forgotten War: Korea: 1950-1953 (hereinafter FW, because life is too short) should also check out the entries in this tag for ASL products that use FW components, which mostly means more Korean War scenarios for you to get your grubby little mitts on. It should be noted that some of these products, as well as at least one (as of this writing) upcoming product, were able to be designed and/or released when they were by third party publishers because either they had a contact among FW playtesters who slipped them pre-publication copies of the rules and boards or because, in one case, the designer was himself a FW playtester and thus had access to such materials. At the same time, MMP refused requests to share draft copies of the FW rules with designers who actually wanted to use them to submit designs or projects to MMP. A little ironic.

History

FW has a long history. Like several official ASL products, its origins stretch back nearly 20 years.

The first ASL attempt at expanding into the Korean War arena came in the late 1990s with the third party publisher Kinetic Energy, run by Mark Neukom and Mike Reed. At the time, they were one of the hottest and most popular third party publishers, primarily because of their high production values (for that era). Kinetic Energy decided to take on the Korean War by publishing two modules–the first would focus on the early months of the war and feature the Americans, and North and South Koreans. The second would introduce the Chinese and the remaining UN forces.

Kinetic Energy put together a set of draft rules as well as a set of scenarios, which they began sending out to their fans for playtesting. They also–and this may sound a wee bit familiar–created four geoboards to go along with the module. These boards showed up the 1998 ASLOK tournament, where attendees got to see four partially-geomorphic hill boards that could be put together to form a massive four-board hill.

Kinetic Energy apparently had concerns about publishing the module itself; according to a 2006 comment by Mike Reed, he and Mark Neukom actually submitted their module to Avalon Hill for consideration for publication. However, according to Brian Youse, Avalon Hill at the time had no interest in moving ASL past 1945. Moreover, in the late 1990s, Avalon Hill was on its last legs as a wargame publisher and it soon sold most of its intellectual properties (including ASL) to Hasbro. Eventually, MMP–who had for several years been Avalon Hill’s development team for ASL–was able to secure a licensing agreement with Hasbro to continue producing ASL products. But by this time, Kinetic Energy’s Korean War project had stalled; in 1999, Mike Reed described it as being “in a coma.”

At some point Critical Hit made a bid to acquire the Korean War project from Kinetic Energy, which Kinetic Energy refused. MMP, too, reached out to Kinetic Energy, according to two MMP principals at the time. One of them, Brian Youse, reported in June 2000 that “We spoke, briefly, with Mark Neukom about Korea, and in ‘sports’ terms we are far, far apart in price.”

One problem was that Mark Neukom was in the process of “divorcing” himself from ASL–he left the hobby and thereafter refused all requests for permission to sell or reprint any of his ASL works. However, the other Kinetic Energy principal, Mike Reed, was still interested in doing Korea for ASL. In the early 2000s he had begun work on such a project, claiming that he was starting over “from scratch,” because of Neukom’s unwillingness to part with KE intellectual property. Given things like the Kinetic Energy Korea hill boards, it’s an open question as to how much was initially done “from scratch,” versus simply re-imagining Kinetic Energy concepts. Reed, who was a playtest manager for MMP at the time, wanted MMP to publish the project as an official module. By 2002, Kenneth Katz had joined Reed in his “from scratch” Korean War project. By November 2002, then-MMP spokesperson Keith Dalton officially announced an intention to publish the project, which he described as “not an updating of [Kinetic Energy] efforts but “an entirely new look at the Korean War in ASL terms.”

Over the next few years, Mike Reed and others gave hints at the development of the Korean War module, which proceeded extremely slowly, apparently at least in part because Reed’s work commitments took him around the globe. In 2004, Reed described work on the project as “slowed down to a crawl.” The Chinese Communists were originally described as a “tweaked” version of their “WWII selves.” However by 2005 it was revealed that the Chinese would have “infantry platoon movement.”

In July 2007, MMP spokesperson Chas Argent stated that the Korean War module was “still deep in the heart of playtesting/development,” but in September of that year, promised that “the playtest for the remaining Korea scenarios is being ramped up as we speak. Only a few of the new rules are still in flux.” Around this time, Kenneth Katz made a public plea for more playtesters. In late 2008, MMP shared some examples of Korean Module counter art:

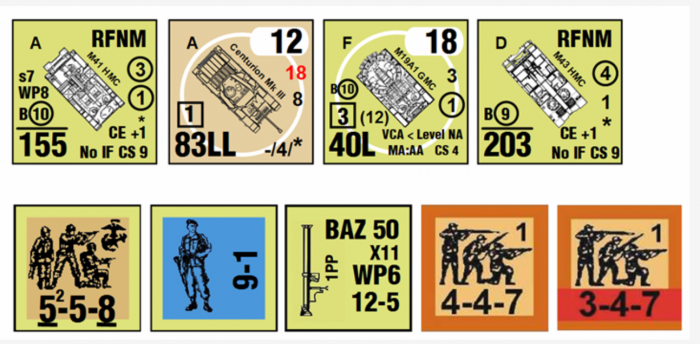

MMP Korean War draft counters

The Korean War module was expected to be officially submitted to MMP in the first half of 2010, but the deadline was not met. Eventually, however, they did submit a product. It either still needed extensive work or merely sat on the MMP backburner, because it was not until 2014 that MMP promised the module would go up for pre-order that year. MMP didn’t meet its own deadline in this case; the Korean War module, now with a name, became available for pre-order only on December 29, 2015. However, even then the product did not come out quickly; it was not until early 2018 that FW actually got into the greedy little hands of gamers. It was not only an odyssey longer than the Korean War itself, it was also an odyssey considerably longer than the length of the television series M*A*S*H.

Counters

So, now that it has been published, what is FW actually like? Let’s start with the counters. The good news is that there are a lot of them—over 1,700. The bad news? Well, let’s just say that if you are one of the negligibly few ASLers who really love two-toned counters, this is the module for you.

The counters themselves are up to their usual late 2010s MMP quality, which is to say high. The die-cutting on some of the sheets is very deep, so the counters may fall off their trees at even a slight touch–something to keep in mind in order to avert possibly losing a counter or two before organizing them in your preferred storage system. Given the nature of the Korean War, it should come as no surprise that the vast majority of the counters are 1/2″ counters rather than 5/8″.

Here’s a quick rundown of the main components of the seven included countersheets:

Sheet 1: This sheet is mostly American, British/Commonwealth and North Korean infantry and SW. Most American troops are represented by counters from Yanks (much more on that in the section of this write-up on Rules). However, there are 6-6-7 airborne squads (half-squads are assumed in this write-up for all squad types), 6-6-8 Ranger squads, and 4-4-6 and 3-3-6 KATUSA squads (Korean soldiers attached to U.S. Army units). The countermix includes plenty of recoilless rifles, as well as a new LMG type (2-8) and a 1950 BAZ. The British/Commonwealth units use British counters/rules but now also have a 6-6-8 Commando squad. North Korean units in FW are mostly represented by Soviet units from Beyond Valor, but they do include leaders with Korean names.

Sheet 2: This sheet is all Chinese, who are represented by the first of the Dreaded Two-Tones. The whole sheet consists of squads and half-squads. Chinese troops in FW use two-toned counters featuring a Soviet-brown exterior and, for some reason, a British khaki interior. It’s not at all clear why they are two-toned, instead of having their own color. It does not seem to be in order to use Soviet SW, because they are given their own SW. It should be noted that the two-toned counter strategy adopted in Gung Ho for the Nationalist Chinese was done so as a perceived necessary evil, rather than from any positive advantages or aesthetics. Two-toned counters are ugly and it would have been far better for MMP to have given the Chinese Communists their own color. The Chinese Communists come in 6-2-7, 5-2-7, 4-3-7, and 3-3-7 striped-back squads, as well as 3-(1)-7 and 4-(1)-7 grenadier squads, all of which will be discussed in more detail below.

Sheet 3: The third countersheet is approximately 50% Chinese and 50% South Korean. The Chinese counters include crews, SW, ? markers, and leaders. The South Koreans–who are another decidedly ugly Two-Tone force (in this case, with a U.S. olive exterior and a khaki interior, essentially resembling vomit)–have on this sheet SW, ? markers, and some heroes. Since the South Koreans have their own SW, there appears to be no valid reason for a two-toned color scheme.

Sheet 4: This sheet is all South Korean, in all their lime-tan glory. This includes 5-5-7, 4-4-7, and 3-3-6 squad types, as well as 5-5-8 and 4-4-8 Korean Marine squad types (MUCH on this later). There are also crews and leaders here.

Sheet 5: Here the purchaser gets to see his THIRD new set of Two-Toned counters. These are for the “Other UN Forces,” and represent a wide variety of units, from French to Turkish to Ethiopian. Do they get their own color? Hell, no, they don’t get their own color. Instead, they have two-toned counters with a U.S. olive exterior and a French blue interior–another spectacularly ugly combination. The U.S. provided most of the equipment for these smaller contingents, but the “Other UN Forces” here have their own SW, so once more there seems to be no good reason for the two-toned counters. To reiterate: two-toned counters ought to be a last resort, not a first resort. This sheet also has South Korean AFVs and trucks.

Sheet 6: This sheet includes “Other UN Forces” miscellany, including half-squads, crews, leaders, ? markers, and SW. It also includes South Korean Guns and American AFVs.

Sheet 7: The only all 5/8″ countersheet, this sheet provides North Korean vehicles, Chinese Communist guns, British vehicles and guns, and American vehicles, guns, and planes. It is on this sheet that one gets to see a bevy of British Centurion tanks, with their 83LL MA and 18 AF frontal armor. You’ll note “Chinese communist guns” are mentioned here, but not Chinese communist vehicles. That’s because there are no Chinese armored or non-armored vehicles portrayed in FW, a perhaps questionable decision. It’s not really important whether Chinese trucks made it into the countermix, because the Chinese had few and these were basically used far from the front, in logistical roles. The question of armor, given its importance to ASL and ASLers, is another matter. Did the Chinese have tanks in Korea? The answer is yes, they had hundreds of tanks in Korea during the Korean War. Beginning in the second half of 1951, the Chinese moved several tank regiments into Korea and kept from 4-6 such regiments (not always the same ones) in Korea until the end of the Korean War. These were mostly armed with T34-85s and SU-76s, with a small number of IS-2s’s and ISU-122s. These units were primarily kept in reserve rather than used in combat the way the North Koreans used (and used up) their own T-34s. However, Chinese sources record several instances in which they allegedly were used in combat and historian Shu Guang Zhang, author of Mao’s Military Romanticism: China and the Korean War, 1950-1953, using some of those sources, mentions two specific such incidents in November 1951.

Even if those encounters did not take place, the mere presence of hundreds of Chinese Communist AFVs should be represented in Forgotten War, even if only for DYO purposes, because they were there. One should not ignore the presence of hundreds of AFVs in a conflict zone. It is worth remembering that Hakkaa Päälle!, the Finnish core module, even provides counters for single-vehicle prototypes. Here, hundreds of AFVs can’t get a moment of respect. Until MMP rectifies this situation, players will have to use Soviet AFVs to represent these forces.

Geoboards

A full module would be nothing without new geoboards, right? Forgotten War certainly has geoboards, but many ASLers may be disappointed in what they get. First, they only get 4 geoboards (80, 81, 82, and 83). One might contrast this to the 7 geoboards in Rising Sun, the 8 geoboards in Yanks, or the 10 geoboards of Beyond Valor.

Moreover, the geoboards that are included are quite disappointing, especially in their lack of variety, because all four boards are essentially the same board. Each board is a partially geomorphic board (geomorphic on two sides, non-geomorphic on the other two) featuring a large straight hill mass with various outcroppings. The non-geomorphic sides are designed to match with the non-geomorphic sides of the other boards so that one can combine all four boards together into an extra-large hill mass like Transformer toys combining into a super-robot. Each board has minor variations in terms of gullies, outcroppings, etc., but otherwise they are basically the same sort of thing. Moreover, the combined hill that they form is boring. Because of the nature of the 8″ x 22″ board type, what you get is basically just a larger version of the sort of big rectangular hill that one can find on a number of existing 8″ x 22″ boards. It’s basically board 9 or board 58 on steroids.

This is rather a shame, because the concept of using partially geomorphic boards to represent certain terrain types of quite valid; it is more the execution that is the problem here. For example, rather than a big long rectangular hill, partially geomorphic boards could have been used to create (when combined) something hitherto unseen in ASL, such as a large roundish or horseshoe-shaped hill, perhaps like, to pick a totally random example, Pork Chop Hill.

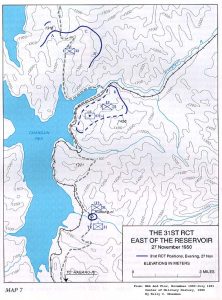

Even on their own terms, the included boards are not ideal. Only one of the four boards, for example, has a road going down its “valley” portion, meaning that one cannot really easily use them to depict UN forces trying to retreat down a road between two ridgelines in which the Chinese control the heights (actions like “The Gauntlet”).

Even on their own terms, the included boards are not ideal. Only one of the four boards, for example, has a road going down its “valley” portion, meaning that one cannot really easily use them to depict UN forces trying to retreat down a road between two ridgelines in which the Chinese control the heights (actions like “The Gauntlet”).

The use of 4 geoboards to form a big rectangular hill would have been more palatable if there had been other, different geoboards in the module to sweeten it. It would have been nice to see a board dominated by non-overlay rice paddies (which would also be excellent for the Sino-Japanese War, as well as some fighting in Burma), or a board with printed fortifications (to help represent some of the 1952-53 actions) or a lakeshore board to help represent actions such as those surrounding Task Force Faith. Alas, these are the “forgotten boards” of Forgotten War.

Rules

As important as the counters and boards are, it is the FW rules that are the most crucial component, defining the nature of the module as well as that of any scenario that will ever be derived from it. The FW rules, as have been shown, had a long history, with some concepts dating back to the original Kinetic Energy Korean War project of the 1990s. Some of the rules are very well thought-out; others less so–or in some cases are even problematic. Whether it is accurate or not, it is hard to avoid getting the sense that much of the rules development may have taken place in an insular environment, with only a small number of people working on them or providing input that might critique or offer a different take on some of the concepts or design decisions made.

Here we’ll go through and analyze (many of) the rules used in FW to simulate the Korean conflict.

Korean War Terrain: In FW, all woods are Light Woods, all grain and rice paddies are Paddy Fields, all roads are dirt, bridges are One-Lane and stone, Cellars are non-existent, and, interestingly, Crag terrain is now both Concealment and Ambush terrain.

Weather: Extreme Weather is possible, as is Extreme Thaw, though the latter does little except reduce the power of minefields.

Bayonet Charges: In the first questionable rules inclusion of FW, the module allows something called a “Bayonet Charge” for all UN Forces (by SSR). This is basically a slightly modified Banzai Charge. If you’re wondering how a Luxembourg or British or U.S. unit might somehow engage in a Banzai Charge, well, you’ve got a good reason to wonder. The reality is that this rule is a legacy of Kinetic Energy, which had a positive passion for “Bayonet Charges,” introducing them all the way back in 1994 in Time on Target #1. Someone–presumably Mike Reed–slipped this concept into FW and apparently no one bothered to fight him on it. The reality is that, for those very few occasions in which something resembling a Banzai Charge or Human Wave attack would be relevant for UN Forces, a designer could have simply decreed that by SSR. There’s no real need for this pet rule in FW.

Variable Time Fuzes: These are proximity fuses, introduced by the U.S. late in World War II, but not previously represented in ASL. Essentially the rules here allow for a sort of “super airburst” that is more effective against some terrain types and less against others. It could easily have been left out, but its inclusion is not really a problem.

Heat vs. AF ≥ 6: This is a rule designed to make Bazookas less effective against thick armor by decreeing that if the HEAT Final TK DR is ≥ 6 when fired at an AF also ≥ 6, then the result is a Dud. This is basically a much, much watered down version of a longstanding Kinetic Energy grudge about armor slope in ASL and has nothing specifically to do with the Korean War. It looks like Mike Reed slipped this one in as well and no one challenged him. Note that for consistency this rule should apply to World War II ASL as well, because armor slopes did not achieve different magical properties in the Korean War.

Steep Hills: The rules for Steep Hills are among the more problematic rules in FW. They are intended to represent some of the effects of the steep-sloped hills that were so common in Korea (and elsewhere, such as Italy). However, they miss their mark badly in certain ways. Based on a conversation your Humble Author had with Kenneth Katz, one of the developers, it seems that this may have ended up the case because the designers were really concentrating on the difficulties that steep-sloped hills imposed on vehicles. They may not have sufficiently considered their effects on Infantry. Steep Hills take up a page and a half of rules, so it is not practical to discuss every aspect of this SSR-imposed terrain condition, but some of their key attributes include the following:

- Open Ground Steep Hill hexes are considered Concealment Terrain and not considered Open Ground for concealment gain/loss purposes.

- Fire to/from a Steep Hills hex to/from an adjacent hex is as if it occurred across a cliff hexside.

- Vehicles may only enter Steep Hills hexes across road hexsides (and roads are all One-Lane). VCA changes cost extra MP or even a Bog Check.

- AFVs with L/LL Guns may possibly not be able to fire at higher-level targets.

- Infantry entering a Steep Hills hex is penalized if carrying ≥ its IPC. If moving up, it must pay triple COT (instead of double); if moving down, it must pay double.

- Guns may set up in a Steep Hills hex but Manhandling into/from one is not allowed.

Many of these rules are innocuous/uncontroversial. However, the rules completely fail to take into account the unusually exposed nature of Infantry on Steep Hills hexes and thus turn a serious vulnerability into a strange strength. Infantry trying to go up or go down steep slopes are drastically more exposed to observation and fire from enemy NOT ON THAT HILL, because they cannot do something like crawling to reduce exposure. A human being crawling up a steep hill may reduce his exposure vis a vis someone higher up on that hill, but presents basically the same amount of target to an opponent viewing him from a nearby hill as if he were standing straight up–because his whole body is exposed. However, in FW, this exposure is not simply ignored but actually reversed by the concealment rules. It is mind-boggling how the rule conveys exactly the opposite effect that it should.

Another effect of steep hills is that more of the hill mass is visible to observers not on the hill; the steep slopes are in full view. In ASL terms, this means that there is a reduced “plateau effect.” In regular ASL hills, a unit on a crest line can be in LOS from someone at a lower elevation, but a unit on any hexes to the rear of that crest line hex cannot. This would not apply with steep hills. Rather, the LOS rules should be worded to allow LOS not only to the crest line hex but also to the first hex beyond the crest line hex, with the plateau effect only kicking in at the second hex behind the crest line hex (if there are any such hexes). But nothing like this appears in FW, so the ostensibly steep hills still have the same plateau effect as the much less steep hills in standard ASL.

A third major effect of steep hills is that it is difficult to fire or use certain weapons in certain directions. It is not necessarily always too hard to fire upslope or downslope but certainly much harder to use weapons such as HMGs at some other sort of target, such as units on a nearby hill. In regular ASL, this is represented in the Crest Status rules, which decree that Crest Infantry firing at targets not within their protected Crest Front must fire as Area Fire and the only SW that can be fired/used are LMG, DC, LATW, or FT. Some similar sort of rule, at least for SW, should be in place for units in Steep Hills hexes, to reflect the fact that, unless one is in a prepared position, such as a Sangar, it is not very easy to set up and fire an HMG while on a steep hill if the target is not further up or further down that same hill. Unfortunately, FW includes nothing like this. The result is a set of Steep Hills rules that simply don’t come near to reflecting reality.

Americans: The Americans in FW are, for the most part, represented by the same units as they are in Yanks, for better or for worse. Actually, the 6-6-6s, 5-4-6s, and 5-3-6s of Yanks better reflect the U.S. Army in Korea than they reflect the U.S. Army in World War II. This is because the first American units moved to Korea were poorly trained, poorly equipped, poorly motivated and in many cases poorly led. Later reinforcing units were often not too much better but thrown into the fray simply because they were so sorely needed. Even later US units, in 1952-53, did not have the motivation levels that most American units in World War II had. So in this sense, the ASL Americans are more appropriate for FW than they actually are for WWII ASL. However, the problems come in with regard to how certain other units are rated (see below).

In addition to the standard US Army squad types, FW introduces a new airborne squad, a 6-6-7. It provides no explanation as to why a 7-4-7 was not used. FW also introduces a new 6-6-8 Ranger squad. It’s a real superhero squad that can Self-Rally, does not Cower, can use RCL without Non-Qualified Use penalties, and use captured weapons without captured use penalties, and can Deploy and Recombine without a leader. They are also Commandos and get to automatically go to the front of the ticket line for any entertainment event. Given that only six (understrength) Ranger companies served in the Korean War, and only for a relatively short time at that, it’s questionable whether there should be a separate Ranger counter at all, but ASLers love their shiny and chrome warboys.

Other “Americans” in FW are actually Koreans–specifically the KATUSA (Korean Augmentation to the U.S. Army), who were Korean soldiers assigned to U.S. Army units. This was an experiment designed to strengthen the understrength U.S. Army units but it is largely regarded as a failure. Language difficulties were simply one of a whole host of factors that kept KATUSA from being satisfactory complements to U.S. troops. In FW, they are represented, appropriately, with 3-3-6 squads for the first year of the war and 4-4-6 squads thereafter. Note that these awful, typically ineffective troops have the exact same morale as standard U.S. Army troops.

American are penalized during the first months of the war because they were particularly unprepared in so many ways. They are Lax, have Ammunition Shortage, have a lowered Repair # for SW, don’t have plentiful ammo for OBA, have lowered Radio Contact, use red To Hit numbers, have a 7 Morale for inherent crews and have red MP for motorized vehicles. This seems appropriate.

In addition to the U.S. Army, the USMC are also represented with 7-6-8 squads and (for re-armed or rear-echelon troops) 5-5-8 squads.

South Koreans: Often ignored, or almost so, in many accounts of the Korean War, except to describe them running away, the soldiers of the Republic of Korea played an important role in the Korean War as one of the major forces and were key in many ways, such as allowing the Pusan Perimeter to form and hold. Still, for a variety of reasons, not least the pre-war limitations on the South Korean army and the sudden way in which the South Koreans were thrust into war, with most of their country quickly overrun, and during the first year of the war in particular, the South Korean forces were among the most unreliable of the coalition fighting the North Koreans and Chinese. In FW, they are represented primarily by 5-5-7, 4-4-7, and 3-3-6 squad types. In isolation, this might not be unreasonable, but the problem here is when compared to their demonstrably better-fighting American allies, who have a lower morale than even 2d-line South Korean troops. This is just not realistic and is similar to the fact that in WW2 ASL, the U.S.’s poorly trained and poorly equipped Filipino allies also have a higher morale than most U.S. troops.

Like the Americans, the ROK troops suffer significant penalties during the early part of the Korean War, with the major difference that the “penalty phase” extends far later for the South Koreans than it does for the Americans.

The South Korean OB also contains one of the more questionable design decisions that can be found in Forgotten War: the inclusion of the “Republic of Korea Marine Corps.” This small force of a few thousand not only gets its own squad type in FW, it actually gets two separate squad types: a 5-5-8 and a 4-4-8. Both are questionably given elite status. It’s really hard to justify the inclusion of the KMC as a force worth having its own counters and rules.

British Commonwealth Forces: The British, Canadian, Australian and New Zealand forces in Korea, which eventually became the “Commonwealth Division” are all represented using British counters and rules. There is one new squad type, a 6-6-8 “Royal Marine Commando” squad, which basically is a superman unit just like the American Ranger squad. The only commando unit in Korea, 41 Commando, numbered only around 300 men and during the war lost only 31 killed, so it is questionable that this tiny unit (which makes the Korean Marines look numerous) deserves a squad type. You can probably chalk it up to ASL’s undue fascination with anything related to Marines. It should be noted that the actual Commonwealth forces also included their own version of KATUSA troops, dubbed KATCOM, but they are not represented in FW.

Other UN Forces: “Other UN Forces” is the somewhat dismissive term used by FW for the Belgian, Columbian, Ethiopian, French, Greek, Luxembourgian, Dutch, Filipino, French, Thai and Turkish forces that fought in Korea, many at battalion strength. They are represented by 5-5-8, 4-5-8, 4-5-7, and 4-4-7 squads. There are few rules distinguishing the national forces, but Turkish units have several special rules, while Ethiopian, French and Turkish leaders are exempt from having to to take a TC to initiate one of the dreaded Bayonet Charges. Of all these, only the French actually show up in a FW scenario.

North Koreans: The North Koreans are well-handled in FW, though given their Soviet-provided training and equipment, history makes it a little easier for ASL designers to model them. The North Koreans use the Soviet squad types–6-2-8, 5-2-7, 4-5-8, 4-4-7, and 4-2-6. They also have are given 3-3-7 partisan squads to reflect the important role that partisan warfare played in Korea, both before the Korean War and during it. The North Koreans also get “Suicide Heroes” which are just Tank Hunter Heroes under another name.

Chinese Communist Forces: Here we come to the most important national force rules, those for the Chinese People Volunteer Army, which are represented in a way that no other force in ASL is represented–though whether that should actually be the case is another matter. These rules may be the most controversial–or at least the most arguable–rules in FW. In essence, there are two related issues here: first, whether the Chinese communists are being portrayed here as they actually were or more as how they were simply perceived by American/UN forces in Korea, and second, whether the Chinese communists were truly as bad as they are portrayed in FW.

Let’s start exploring the second issue first, by examining some of the rules governing Chinese communist forces, and we’ll begin to integrate that with the first question as we go. There is no doubt that the Chinese forces in FW have more limitations and drawbacks than any other national force portrayed in ASL. Are these design decisions warranted? We can look at them on a case-by-case basis, but keep in mind that these effects are cumulative–they don’t exist in isolation from each other.

- Early War KW CPVA: By this rule, all Chinese units suffer from Ammunition Shortage and a lowered SW repair dr in scenarios set from October 1950 through March 1951–in other words, many, perhaps most Korean War scenarios. It is certainly true that the Chinese did not even have their logistical system fully in place when they abruptly changed their intervention plans from defensive to offensive in nature in October 1950 and that the repeated offensives over the next few months, combined with American air attacks, never really allowed them to develop one. Nevertheless, the Chinese did pause between offensive in order to refit, and Chinese soldiers at the beginning of an offensive had more ammunition and supplies than they did one week into such offensives, by which time the inadequacies of the Chinese supply system would typically really have a major impact on front-line units. This key fact–that Chinese soldiers at the start of an offensive were better equipped, armed, fed, and supplied than they were some days into an offensive–is nowhere represented in FW. Chinese squads appearing in scenarios set near the end of offensive actions are just as powerful as Chinese squads on the opening days of offensives. Rather than universally hobbling all Chinese forces with such rules, it would have been better to have had a rule (even perhaps more severe than this one) governing scenarios specifically set after the initial days of their each of their 1950-51 offensives.

- Chinese Squad Types: The Chinese have no elite squads in FW and no squads with a morale of 8. Their primary squad types are 4-3-7 and 3-3-7 squads. These are dubbed “Initial Intervention MMC” and are intended primarily for scenarios set from October 1950 through March 1951. [Here a note of explanation may be in order. Several FW rules refer to this ostensible five-month “Initial Intervention” period. This can be confusing, because it does not correspond to what most historians consider the Chinese intervention period to be, which is from October 1950, when they actually intervened, through May, by the end of which their fifth and final all-out offensive had failed. A UN counter-offensive followed, after which the front solidified and the so-called “mobile” phase of the Korean War was replaced with essentially static defense lines.] In addition to these squad types, there are two “grenadier” squad types with values of 3-(1)-7 and 4-(1)-7. These units, intended to represent soldiers armed mostly just with grenades, have no Long Range Fire or doubling for PBF, and have doubling rather than tripling for TPBF. They may also not Interdict, nor (somewhat oddly) may they use or repair any or Gun. This sort of squad type was probably needed in ASL (and fits other situations, too, such as some Polish units in the 1944 Warsaw Uprising), but with regards to Korea, there is a chance such squad types may be over-used. There are also 5-2-7 and 6-2-7 squad types for “Soviet-armed” squads.

- Chinese Striping: A key aspect to Chinese squads appear on the backs of their counters rather than the fronts. That is to say, Chinese units “stripe,”or step reduce, in ASL just as Japanese units do (i.e., they do not break normally but flip to a reduced strength set of values instead). This is a major design decision that has major effects. Is it warranted? The decision was made in Code of Bushido to use step reduction rules for the Japanese to represent the unique way in which Japanese units during World War II simply refused to surrender but would fight until attrition finally annihilated them. Did the Chinese in the Korean War fight this way? The answer is no, they did not. Chinese troops could be routed in battle; they could also surrender (even en masse) when surrounded. The Chapter W footnotes try to justify step reduction for the Chinese by claiming it represents their “steadfastness under fire and in the face of high casualties,” “the lack of effective communications to modify or call off attacks once started,” and “unarmed or poorly armed troops in the unit picking up the weapons of their fallen comrades.” These are not good justifications. The Chinese were indeed often steadfast under fire–but so were countless other troops not represented in ASL through step reduction (including Waffen SS). Every nationality during this era suffered (either always or from time to time) a lack of effective tactical communications. And “unarmed/poorly armed” troops are already represented in FW through the grenadier squads. These are all weak justifications when compared to the effects that the culture of bushido had on the way Japanese units operated. It is hard to justify giving Chinese troops step-reduction.

- Chinese Leaders: The Communist Chinese have one of the worst set of leaders in all of ASL. Their leaders are 10-1, 10-0, 9-1, 9-0, 8-1, 8-0, 7-0, and 6+1. They have a single benefit: unpinned GO leaders increase the Morale Level of MMC in their location by one. So, to start, the Chinese do not get 10-3, 10-2, or 9-2 leaders. Even the Japanese get a 10-2 leader. The Finns also have a “lesser” set of leaders, but their worst leaders are 8-0 and 8+1 leaders. Moreover, all Japanese leaders get the full “commissar” effect, while Finnish squads are self-rallying, which makes up for their worse leaders. Basically, the Communist Chinese are being cheated here. Their forces in Korea were veteran forces, fresh from their victorious fighting in the Chinese Civil War, with many leaders having also had experience fighting either (or both) Japanese or Nationalist forces during the 1937-1945 periods as well. Some seasoned veterans may have even had combat experience dating back to the 1920s. The Chinese communists had no shortage of battlefield leaders, not by a long shot. In FW, however, they are treated as crap. This is not justifiable.

- Concealment & Stealth: Chinese communists in FW are Stealthy if Good Order; they also receive a -1 drm to their Concealment dr. In an interesting rule, their Infantry may attempt to gain Concealment (if in Concealment Terrain) even if in LOS of unbroken enemy ground units, as long as there is at least a +2 Hindrance DRM. This is a realistic rule because not only did UN forces perceive the Chinese as being particularly good at camouflage and stealth, this is something the Chinese themselves actually emphasized and trained on. The Chinese may also get 10% HIP (25% at Night), just like the Japanese.

- Restricted Fire: This is one of the worst rules in all of ASL. By this rule, all Communist Chinese units firing at non-adjacent targets during the Prep Fire Phase (or when using Opportunity Fire) have their attacks treated as Area Fire (i.e., halved), unless the attack is directed by a leader. This rule, by itself, makes the Chinese worse than every other Nationality represented in ASL. The FW footnotes don’t even attempt to justify it, either. Again, it is important to understand that the Chinese communist force in Korea was, by and large, a veteran force that just came out victorious from one of the largest conventional wars of the 20th Century (the Chinese Civil War). They knew how to fight. The notion that their firepower should be halved unless a leader is there to direct it is just crazy. The Nationalist Chinese don’t have this restriction. Soviet conscript squads don’t have this restriction. Slovak conscript puppet troops don’t have this restriction. Excuse us, we are getting so worked up we have to go take a Xanax. And maybe some wine.

- Infantry Platoon Movement: The “restricted fire” rule mentioned above is part of a rule dubbed “Command & Control.” The other main part of the “Command & Control” rules are the “Infantry Platoon Movement” rules, which are another set of rules designed to straitjacket the Communist Chinese. Under these rules, Chinese units must move in clumps, each containing a leader–or else (with a few exceptions) they almost cannot move at all in the Movement Phase. They are sort of like more-controlled Human Waves, only without most of the advantages. Moreover, units using IPM (which, again, will be most Chinese units) cannot mount/unmount vehicles, dash, search, set DCs, engage in Clearance, or Push a Gun, among other restrictions. An MMC can only engage in non-IPM movement if it passes a NTC; if it fails, it can only move one Location. There are some exceptions to the NTC; an NTC is not required if a unit moves with a leader, has a DC or FT, is Fanatic, is Cloaked, or qualifies for certain other exceptions. Needless to say, these are incredibly restrictive (and may be especially problematic for certain types of scenarios such as a Chinese fighting withdrawal scenario). What is more, they appear to be rules based more on how Americans (& others) perceived, or in some cases misperceived the Chinese, rather than the way the Chinese necessarily always actually fought. Now, to be fair, the FW footnotes admit that, though there was a perception of the Chinese as using “massed waves of screaming soldiers,” this was not accurate. Nevertheless, FW still treats the Chinese with a “lite” version of that perception. It is clear that the designers of FW think the Chinese had little in the way of tactical abilities. It is certainly true that the Chinese Communists began as a partisan army with little knowledge of advanced tactical techniques. However, it is also true that during the Chinese Civil War, the Chinese communists made serious attempts to professionalize their military and increase their warfighting and tactical abilities. In fact, this was a key reason they were able to defeat the Nationalist Chinese. This emphasis on better tactics began in the fighting in Manchuria and reached their peak during the major Liao-Shen Campaign. A key aspect to this was the so-called “Big Training” program conducted for months during the summer of 1948 in order to better allow Chinese soldiers to conduct mobile operations and combined-arms operations without suffering undue casualties, and which included training for company and platoon leaders, so they could impart these techniques to their units. As one Nationalist Chinese general wrote to American General Albert Wedemeyer as early as August 1947, “They are now fighting as regular army do…They have abandoned the 18th century assaults, and they have adopted the dispersed attack.” It is really hard to justify mandating Infantry Platoon Movement for veteran Chinese communist forces while not mandating the same for Soviet units rapidly mobilized in late 1941 and early 1942 and thrown into battle virtually untrained, for Romanian units crudely attacking near Odessa in the summer of 1941, or for Volkssturm units or many other units far less trained and veteran than the Chinese Communists (and with as little “command and control” capabilities). The Infantry Platoon Movement rules are another example where the Chinese communists are unfairly treated.

- Night Scenarios. The FW rules also provide chromey rules for Chinese “bugles” being sounded during Night actions, which can give a -1DRM to non-IPM movement TC for the Chinese and can produce “Jitter Fire” for their opponents. More night rules for little good effect are probably not needed. These rules are among a number of new Night-related rules for FW, the longest of which are the Searchlight rules, which are an amazing 2.5 pages long. On Searchlights. Yikes. This actually brings up the issue of missed opportunities. The Night Rules are unpopular in ASL, with many players refusing to play Night scenarios and others only doing so reluctantly. This is probably due to the combination of several fairly complex rules (including Cloaking and Illumination) as well as a host of other, minor rules diverging from regular ASL play that are not necessarily individually complex but are hard to keep in mind all at once. But Night actions are very important in FW, primarily because the Chinese chose to launch most of their attacks at night (in order to minimize American advantages like firepower and air support). FW presented a perfect opportunity for MMP to revise the Night rules, replacing the original unpopular rules with a more streamlined, easier to remember and easier to play set of rules. That would have benefited all ASLers, not just those playing Korean War scenarios. However, MMP did not avail itself of this opportunity. One result of that is that we now not only have bugles but now must memorize rules for Illumination Beams and Searchlight Sighting Task Checks (which can have 15 different DRMs). Oh boy.

- OBA: For some reason, FW does not give the Chinese communists OBA until June 1951. The footnotes do not explain or justify this decision. It is true that most division level Chinese artillery were used in direct fire roles, but the Chinese Communists had acquired the ability to use indirect fire for their artillery back in the Chinese Civil War.

- Last Word on the Chinese: The Chinese were created for FW with a heavy hand, with most of the heavy-handedness going to make the Chinese Communists seem primitive and of low ability. It’s worth nothing that these “primitive” Chinese handed the U.S. Army some of the worst defeats in its entire history. The Chinese in FW also suffer from a fair degree of lack of differentiation. The Chinese Army in Korea was not a monolith. There were sometimes significant variations even from army to army (Chinese “armies” were actually corps-sized). One type of differentiation not represented here at all was that some of the Chinese units (most famously the 50th Army) were actually originally Chinese Nationalist Units that had changed sides and begun fighting with the Communists–typically with their original weaponry and training. The great variations of fighting condition for Chinese units depending on what stage they were in during an offensive is also, as mentioned above, not modeled in FW. However, FW does represent later Chinese units that had Soviet weaponry.

Air Support: FW adds a 1950 FB and an AD Skyraider (both for UN forces only, obviously). However, the major change to the Air Support rules is in the addition of Forward Air Controllers, which come in three varieties: USMC Tactical Air Control Parties (a special type of crew), Offboard USMC TACP, and airborne Forward Air Controllers. The Parties have inherent radios that can be used to direct Ground Support attacks. This helps with Sighting TC and creates an Immunity Zone around the TACP that cannot be attacked with a Mistaken Attack. The offboard TACP provide a similar effect without any counters on the ground. Given the limited effects, one has to wonder whether all FAC might better have been handled that way. Airborne FAC represents an airplane in the vicinity acting as observer. It is kind of like a moving offboard TACP. Thankfully there are no extensive rules dealing with jet fighters or helicopters.

Tunnels: Finally, one area where I expected rules but found none. Was a little puzzled to note no rules in Forgotten War to treat the extensive use of tunnel systems by the Communist forces in Korea in 1952-53. They don’t quite seem the same as either current one-off ASL tunnels or caves, but not even a mention of them here. A bit odd.

Forgotten War also comes with extensive Chapter H notes for UN and Communist forces (26 pages for the former and 10 for the latter). Most of the vehicles and guns that appear in FW previously appeared in World War II, but FW includes them here rather than simply referring players back to their original Chapter H entries; this is a good thing. However, the Chapter H pages still continue the practice of “multi-applicable vehicle notes,” meaning for most entries players will have to go to multiple different pages to get all the rules for a vehicle or gun. This is a really inconvenient practice that should be abandoned. A player should be able to consult a single location to get everything he needs in order to use that vehicle or gun. Among the new entries, however, notable appearances include the M32A1B3 Tank Recovery Vehicle, for those ASLers interested in armored tow-trucks; the M46 “Patton” Medium Tank (not to be confused with later tanks also dubbed “Patton” tanks, this was basically just an improved Pershing tank); a jeep with a mounted 105mm RCL (which seemingly can’t be removed); the British Centurion III tank, with its 83LL gun; and a revised British 3-inch MTR (which appeared in ASL as a 76mm MTR, but subsequent research suggested they were actually of 81mm caliber, something that is fixed here, along with a note that says they can be used in scenarios set after August 1942). Communist forces’ entries include a Type 51 Rocket Launcher, which is a less effective Chinese-made clone of the American M20 bazooka, as well as similarly inspired 57mm and 75mm RCL. The Chinese oddly only get one model of AA gun, even though by the end of the war they had deployed huge numbers of AA guns in Korea. Were they all this model?

As a side note, it would have been handy for US and British counters that only appear in FW (and not in WWII) to have a “K” or “FW” somewhere on the counter. That way, for players who may simply add FW counters to their standard countersets, one can more easily ignore such counters when searching for WWII counters.

Scenarios

FW comes with 16 scenarios (203-218; nothing in their designation makes clear that they are Korean War scenarios). The scenarios are mostly large (or very large) in size: 10 large/very large scenarios vs. 2 medium and 4 small scenarios. The scenarios also tend somewhat to the longish. Somewhat surprisingly, virtually every scenario (15 out of 16) are set in the first year of the war.

The scenario mix is very Yank-centric. The 16 scenarios include 5 U.S. vs. North Korean scenarios and 5 U.S. vs. Chinese scenarios. There are also 3 British vs. Chinese scenarios as well as one French vs. North Koreans scenario. The force that really gets the short end of the stick are the South Koreans, who only appear in two early-war scenarios vs. North Koreans, despite being one of the largest combatant forces throughout the entire war (and despite several English-language books describing ROK actions).

Boards required to play all the scenarios include: 2, 8, 9, 10, 15, 17, 18, 19, 23, 24, 33, 37, 43, 44, 50, 61, 80, 81, 82, and 83. This board mix allows a couple of observations, the first of which is that (leaving aside the FW boards [80-83] themselves) only one board used in a FW scenario is not one of the first 52 boards issued by AH & MMP (the only ones ever published as mounted boards). This suggests that most of the FW scenarios were designed many years ago. Second, only 6 of the 16 scenarios use any of the boards included in FW, which may highlight their limited utility.

Not surprisingly, a third of the scenarios in FW are Night scenarios, so you’d better brush up. Four scenarios use OBA rules while one scenario uses Air Support rules. Three scenarios use the unfortunate Steep Hills rules.

Nine of the 16 scenarios feature large or massive North Korean or Chinese forces attacking much smaller defending UN forces.

Many of the scenarios featuring the North Koreans are among the most interesting. There, one (usually) does not have to worry about Night rules, nor about Infantry Platoon Movement. Even the scenarios featuring large North Korean attacks don’t typically have the huge numbers that some of the Chinese scenarios do.

Perhaps not surprisingly, the North Korean scenarios are among the most-played scenarios in FW. Given the desperate fighting both during the U.S./North Korean retreat and later along the Pusan Perimeter, it may well be that North Korean scenarios in general (whether appearing in FW or elsewhere) end up being the most popular variety of Korean War scenarios.

Of course, popularity is relative. The recent MMP HASL, Hatten in Flames, which came out later than Forgotten War, has so far had 306 playings of its 8 scenarios recorded on the ROAR website. The 16 scenarios of Forgotten War, have to date only had 207 playings recorded. How much of this relative lack of interest has to do with a lack of interest in the Korean War itself, a lack of appeal on the part of FW rules and components, and/or a lack of interest in the specific scenarios that come with Forgotten War is hard to say.

Bottom Line

Texas newspaper columnist Molly Ivins liked to describe U.S. President George W. Bush–of whom she was definitely not a fan–as “the only president we’ve got.” That may not be a bad way to describe Forgotten War. The good news is that ASL now has a set of rules and components for playing Korean War scenarios using the ASL system. The bad news is that it’s Forgotten War. It’s the only Korean War module we’ve got.

That is rather unfortunate, because so much of the decision-making that went into Forgotten War, from art decisions (bevies of two-toned counters and the big rectangle hill board collection) to design decisions (steep hills, incompetent Chinese) are legitimately questionable. If this were a third party product, it wouldn’t matter very much at all, but this is “official” ASL, so many of these decisions are now essentially set in stone.

Certainly there are things to like here, or at least not to complain about. The North Koreans and the South Koreans (except for the two-toned counters, and the latter’s Marines) are well-rendered. Aside from the colors of their counters, the “Other UN Forces” also seem to be reasonably well thought-out. The Chinese grenadier squads are a good addition even if some of the other rules about the Chinese are not. And certainly a number of the scenarios are balanced and some may even be fun, on their own terms.

Nevertheless, one can’t but come away with the impression that there were missed opportunities here. Opportunities for better color schemes, for more–and more interesting–boards, for a model of the Communist Chinese that didn’t penalize them so much (and which could also allow their use in Chinese Civil War scenarios). Opportunities to improve the Night rules and to more realistically represent the effects of the steep hills of Korea.

Still, it’s the only Korean War module we’ve got.

While I passed on this one (not too interested in the conflict, too much WWII ASL left, too little $$), I am interested in your general criticisms of the night rules. I do find that like the rest of Ch E, they are somewhat poorly written, but (for me anyways) you do get a pretty fun and not illogical experience out of it.

So how would you improve them? Do you think that as written they create ‘unrealistic’ situations? Or is it that they just need a rewrite?

At any rate, thanks for your hard work, and keep it coming!

That was a far longer and surprisingly negative review than I expected. I understand, however, that you found a lot with which to disagree. My knowledge of the conflict is not sufficient to contest any of your reasoning. The Bazooka rule is obviously there for the reason you described. Thanks for your work.

Well, I’m one of those that has yet to play anything from Forgotten War. It’s not due to a lack of interest in the conflict; but rather time constraints and not wanting to deal with the extra rules complexity. So that’s one data point for you.

One rule that really turned me off to KASL was its use of Light Woods. This rule seems to grant all the benefits of full Woods to the attacker, while allowing them the ability to completely mess with rout paths. Unfortunately other TPP seem to have adopted this rule in many of their scenarios as well. I am at the point where I will not play a scenario that contains the,

By 1950, Korea was a rather barren land, and the use of Light Woods accurately represents the terrain as it was.

The Japanese denuded Korea of its trees during their long occupation of the peninsula. Thus by 1950 the trees were mostly young grow. Even when I was stationed there in 1985, and went out in the field much, there were very few stand of trees with the underbrush that we in the US wood call woods. Also, the South Koreans harvested brush constantly to burn. The light woods rules are very appropriate for this conflict.

Accurate as the terrain may be, I find Light Woods to be one of the worst rules in ASL and have many (much more enjoyable) scenarios to play that don’t include them. Now if you want to substitute Steep Hills as another reason I won’t play KASL I’m fine with that too…

I love light woods. I am going back over my scenario designs and a looking for opportunities to insert light woods as errata.

Just kidding about that last part. But I love light woods.

I was one of the five core members of the design team for Forgotten War. I do appreciate Mark’s thorough and detailed review, although I disagree with many of the specific points. I have written a detailed response and posted it on GameSquad.

The complete response, originally posted on GameSquad.

On behalf of the Forgotten War design team, I want to respond to Mark Pitcavage’s recent review of that module on his highly regarded ASL website Desperation Morale. Obviously, we have a protective attitude towards Forgotten War. Its development dominated much of our free time over the years (for some over 18 years!) and Mark’s critical review is less then pleasing to us as a team. However much we disagree with elements of the review, we want to commend Mark for his thorough critique.

The Forgotten War core design team consisted of Mike Reed, Ken Katz, Paul Works, Andy Hershey, and Pete Dahlin. Each brought a very strong skill set to the team and our differing styles and capabilities meshed well. The Forgotten War extended team included approximately thirty additional participants from across the globe; all such participants were included in the Korean War ASL Yahoo Group and had access to all development material, to include the rules. Any intimation (or direct statement) that development was done in isolation is false.

Mark’s discussion of the history of the product is generally correct up to a point but does not accurately describe the relationship between Forgotten War and the Kinetic Energy ASL module which was never published. It is true that one of the co-designers, Mike Reed, worked with Mark Neukom on the Kinetic Energy design and we are certain that earlier work influenced Mike’s contributions to Forgotten War. Personally, my only connection with the Kinetic Energy design was a 5-minute glance at it. The major design elements of Forgotten War, including Steep Hills and the CPVA rules that we created, did not come from Kinetic Energy. This is true for all the other core Forgotten War team members as well. Furthermore, the Kinetic Energy style did not mesh well with MMP’s vision for ASL, so a new design was necessary since a primary of objective of this project was to design a product that would become “official.” MMP put the product under contract in 2011. It then waited in MMP’s development queue for several years, with intensive work resuming around 2015 and publication in late 2017.

Steep Hills and Semi-Geomorphic Mapboards 80-83:

Korean terrain had a tremendous influence on the conduct of the Korean War. Through research, it became apparent that the existing variety of ASL terrain types did not represent the tactical effects of much militarily significant Korean terrain. The result was the Steep Hills rules (W1.3), which could be described in a nutshell as doing to Hills what the Dense Jungle terrain does to Woods. The essential requirements of Steep Hills were to deny off-road movement for vehicles, burden infantry movement particularly by heavily laden troops, and provide some protection because the terrain is broken. Note that such terrain is not unique to Korea. Terrain with such characteristics can be found in places as diverse as Afghanistan, Italy and Israel. The use of Steep Hills terrain puts a premium on infantry and greatly restricts the use of heavier support weapons and vehicles, which is accurate for many Korean War battles. The mapboards not only represent the hills and valleys which were the sites of many Korea War valleys, but the topography of those mapboards combined with the Steep Hills rules mean that there are ample opportunities for an attacker to infiltrate and withdraw while being protected from enemy fire. Using Forgotten War boards and Steep Hills terrain, a defender cannot just sit on peaks with a MG and sweep the hill clean of attackers, and that was very much the intent. Taken as a whole, the rules and mapboards provide the “design for effect” that was intended and reflected the team’s research.

Chinese People’s Volunteer Army (CPVA):

Probably Mark’s most serious objection to the Forgotten War design is the CPVA. Before addressing the finer points of the CPVA rules (W7), we should preface our responses with several “big picture” points. The CPVA was a major combatant that fought in distinctive ways that deserves distinctive nationality characteristics. All nationality characteristics are exaggerated stereotypes, but that does not mean that they don’t have a significant element of truth. The best way to appreciate the CPVA in Forgotten War is not to focus on each rule but to see how the totality of the CPVA rules, the scenario orders of battle, and the scenario victory conditions combine to incentivize the CPVA player to fight the CPVA in accordance with its distinctive doctrine and tactics. The portrayal of the CPVA in Forgotten War was based on extensive research that utilized a wide range of sources. These included numerous historical books/narratives by Western (U.S., British, Canadian, French, Belgian, etc.) authors using multiple original sources; U.S. Army historical documents, to include multiple, previously-classified documents; U.S. Army operations research books/documents that included analyses of operations and interviews with CPVA personnel; South Korean historical documentation; and multiple books by Chinese authors. The CPVA’s representation was available to the entire, extended Forgotten War team. Scenarios and Chapter H content were informed by a Chinese-speaking team member that had access to additional Chinese-language source material.

The intent of the portrayal of the CPVA in Forgotten War was to represent several characteristics of that force: its mass, its willingness to tolerate very high casualties, the primitive nature of its communications and logistics, and its tactical doctrine which emphasized closing with the enemy. The latter both leveraged the strengths of the force and reduced the ability of its enemy to use its superior artillery and airpower. In the interests of brevity, we won’t take a deep dive into every rule, but we believe that to those who understand the CPVA and the CPVA rules in Forgotten War, the logic behind the rules makes sense. Needless to say, far from denigrating the CPVA, the Forgotten Warrules and scenarios in combination show the CPVA to be a formidable foe.

CPVA Step Reduction:

The following represent the primary reasoning elements we used to select Step Reduction (W7.21) to represent the CPVA. Taken individually they are evidential and indicatory. Taken as a whole, and leveraging existing ASL rules constructs, Step Reduction was the answer.

Prisoner ratio. Using estimated casualty numbers, we have the following historical percent-of-casualties data (i.e., these percentages show the percent of total casualties that prisoners represented): Allies WW2 (Pacific Theater) 24%; Japanese WW2 2.2%; CPVA KW 2.8%. Although more than moderately suggestive, these estimates do not address a number of related considerations (such as the huge number of Chinese troops freezing to death vice being combat casualties).

Numerous personal narratives from KW participants about CPVA troops weathering huge amounts of firepower and still coming. Sort of like being berserk in ASL, except they were not berserk and could change what they were doing when commanded to do so (i.e., they did not just always charge right toward the nearest enemy).

Accounts of many CPVA soldiers, who would begin a charge/human wave (HW) unarmed, picking up the weapons of their dead/wounded comrades and continuing forward. Some similar accounts appear in descriptions of Russian HWs (in Stalingrad, for example); in the CPVA case, however, the descriptions do not describe large numbers of Chinese troops breaking. Going to ground and melting away, yes. Large groups of them breaking and running away (like what can result in a standard ASL HW), no.

The political indoctrination and presence of POs in even the smallest units had a major impact on how the CPVA troops behaved. They were more motivated by such indoctrination than typical Russian troops and were motivated as such to continue on in the face of significant casualties.

Step Reduction is an existing ASL rule that will be familiar to most intermediate- and advanced-level ASL players.

Initial Intervention:

CPVA Initial Intervention squads represent troops armed with weapons obtained from the Nationalists (GMD) and the Imperial Japanese Army. The Soviet-Armed squads represent troops armed with Soviet weapons, primarily “burp guns,” which is what Americans called the Soviet-supplied PPSh submachine gun and its Chinese-manufactured version Type-50. The dates given in W7.12 and W7.13 are a simplification; the Soviet-Armed squads will not be available before April 1951, but the Initial Intervention squads obviously do not all instantly disappear or rearm after that date.

The CPVA that intervened in late 1950 in Korea lacked any significant amount of radios and motor transport. In general, CPVA troops on the front line during that period suffered terribly from cold, hunger, and lack of ammunition, the latter being exacerbated by the wide range of ammunition types used by the variety of weapons in the CPVA arsenal. That primitive and deficient CPVA communications and logistics generally caused the effects portrayed in W7.11 is no surprise. Nor is the absence of OBA during that time period surprising, given that artillery is particularly dependent on good communications and ammunition supplies. Of course, a scenario designer can add an SSR when these generalizations did not apply.

Leadership:

The CPVA leadership model in Forgotten War (W7.3) is not a slight against the quality of CPVA leadership any more than similar leadership models are intended to denigrate Finnish and Japanese leadership. Again, look at the big picture rather than each element of the module in isolation. The leadership model that was chosen by the designers works well with the rest of the rules for the CPVA.

CPVA AFVs:

Later in the war, the CPVA did have a significant armored force in Korea. However, the only evidence of which we aware that claims this force (as opposed to the odd captured UN AFV being used) was actually engaged in combat with UN forces is traceable to one Chinese claim. We discovered no American after-action reports that describe losses to American armor caused by Chinese AFVs (one suggestive original source claims that Chinese tank guns were firing at U.S. troops; but after care examination of related sources, it is appears these “high-velocity rounds” were from direct-fire artillery). It’s axiomatic in military history that measures of one’s own losses are usually more reliable than claims of losses inflicted on the enemy. We disagree with Mark that including counters for vehicles that were present in theater but never saw combat is a good use of a finite number of countersheet spaces. If a scenario designer chooses to portray CPVA armor in a scenario, he can use Russian T-34/85, JS-2 and SU-76M counters. In addition, MMP informed us that if a counter did not see action it does not go in the box.

CPVA AA Guns:

As the war progressed, the CPVA became well equipped with AA guns. Such AA guns rarely were present in the front line within the scope of a typical ASL scenario. If a scenario designer chooses to portray CPVA AA guns in a scenario, he can use Russian 37mm and 85mm AA guns. Again, finite countersheets forced choices.

Night Rules:

It is true that Forgotten War has a lot of night scenarios for the simple fact that the Korean War had a lot of night actions. The US Army today likes to say that “We Own the Night” because of its excellent technology and proficient use of that technology. But during the Korean War, that technology did not exist and the Communist enemy preferred to fight at night because it tended to negate American advantages in artillery and airpower. Mark does not like the current night rules in E1 and laments that the Night rules were not revised in Forgotten War. But there is an unwritten but very real policy in “official” ASL that new additions to the ASL system must be backwards compatible with the existing system, including counters, rules, and scenarios. Making general ASL changes was simply outside the scope of Forgotten War.

Searchlight Combat:

Searchlight operations played a major part in the later stages of the Korean War. As mentioned previously, the CPVA used massed night attacks to mitigate American firepower and were very effective. The longest retreat in U.S. military history (U.S. Eighth Army in late 1950) was a direct result of effective CPVA maneuver and envelopment…at night. Searchlights took that advantage away from the Chinese.

Our research uncovered that searchlight tactics used against the Chinese were so effective that searchlight-equipped M46 and Centurion tanks became primary artillery targets, especially during the Battles for the Hook. Hide and seek tactics were developed. Tanks operating in pairs or groups. Shutters that could be opened and closed very quickly to minimize highlighting/silhouetting. We worked very hard to replicate these tactics in the rules. Searchlights are certainly chrome. That said, leaving them out or oversimplifying them would have been neglected a tactically significant aspect of the Korean War.

Two-Color Counters:

Mark doesn’t like two-tone counters. De gustibus non est disputandum, but we have been around the ASL community for 25 years and have never been aware of a significant group of players who don’t like two-tone counters (as opposed to the vocal opponents of overlays and terrain altering SSRs). The problem is that the sorts of colors that suit ASL counters (various shades of brown, tan, green, blue, and gray) are already taken, unless you want to either use minor and nearly indistinguishable variations of shade (which some find difficult to see) or use colors which just don’t seem to fit the game. Lavender counters, anybody? Furthermore, the use of two-color counters has other advantages. ROK and Other United Nations Command forces were equipped by the US. Since their counters have a green border like American counters, they easily can use American SW, Guns, and Vehicles. The CPVA counters have a brown border like Russian and GMD counters, and they can easily use both Russian and GMD SW, Guns and Vehicles. In fact, MMP requires designers to fit their numbers of counters within a finite number of countersheets, and two-tone counters for some nationalities reduces the requirements for counters.

Small Forces: Rangers, American Paratroopers, Royal Marine Commandos, and Korean Marines:

Rangers, American Paratroopers, Royal Marine Commandos, and Korean Marines are unabashed chrome. These all were interesting forces that can be represented with very little rules overhead. Mark doesn’t seem to like this kind of chrome. The Forgotten Wars designers disagree. Judging by the plethora of obscure yet fascinating things in the system, so do most ASL players. Rangers and Royal Marine Commandos were true elite special operations troops, and their capability in Forgotten War are indicative of their training. The 7-4-7 American paratroop squads in World War II imply that those troops had a high percentage of submachine gun-armed soldiers. American paratroopers in the Korean War were armed with the M1 Garand rifle and not many submachine guns, hence the 6-6-7 value.

Rules Pertaining to Bayonet Charges and VT Fuzes:

Bayonet Charges were in fact occasionally used by UN forces in the Korean War. The inclusion of the rule in Forgotten War is simple and appropriate. Variable Time (VT) Fuzes for field artillery were first used by the U.S. Army in the Battle of the Bulge. They had an important effect on that battle and were very valuable in Korea when defending fortified positions against massed infantry attacks. Again, the rule in Forgotten War is simple and appropriate.

Rules Pertaining to HEAT and Bazookas:

The ASL armor penetration rules (C7) are fundamentally flawed and unrealistic in that they significantly misrepresent the actual interaction between ammunition and vehicle targets. Unfortunately, it is wildly impractical to do a wholesale overhaul of those rules, given the imperative of “backwards compatibility” and to maintain relative simplicity (if anyone has ever played the fun but very-detailed Tractics they know the issue). But the Forgotten War designers had a problem. The BAZ45, which equipped US Army and ROK troops in 1950, is somewhat effective against the T-34/85 in ASL. However, in 1950 Korea, the M9A1 launcher and M6A3 rocket which are represented by the BAZ45 counter were notoriously ineffective against that target. This is not an issue of chrome. The difference between ASL and historical performance greatly affected certain scenarios and had a real-life tactical impact. As a result, the Forgotten War designers chose to use rules W.8 and W.8A to model this important effect while avoiding an undesirable revision to C7.

Errata:

Players will observe that the astonishingly small amount of errata for Forgotten War is a testament to the combined efforts of the designers, the playtesters, and MMP.

In Conclusion:

The designers of Forgotten War remain confident that they have created an accurate, playable, and high-quality portrayal of ground tactical combat in the Korean War that fits well in the ASL system.

“Or you can read the whole darn thing, like a true American would, by jiminy.”

And a dutiful Canadian, if I may add!

Thanks for the utterly thoughtful review. Perhaps your best. The designer’s response is also a bonus value added, if a little less helpful.

You know, after reading your critique of the CPVA rules you almost got me regretting my purchase. Serious stuff there. But … I always remind myself that ASL is a GAME and any resemblance to real warfare, while truly enjoyable, is also coincidental.

That said, is there enough “flavouring” to make this a Korean War game, for me? Maybe I will post again with an answer.

Many thanks, merci beaucoup!

The more I read about the Korean War , the more examples I see of effective bayonet charges ( Could be a little ‘red car’ syndrome?). This scenario designer is happy to have that rule in my tool kit -and you will see it used in more scenarios.

It is high praise when I design team tries to refute your review. Also its a bad idea, which is why its hardly ever done. The never once addressed an issue Mark brought up except to say, “As a Whole this is how it ought to be.” That is basically saying, “I agree to disagree.” A totally valid stand but not a good rebuttal if someone is critiquing your system in a tangible way. The Steep Hill explanation was the weakest, “We wanted this not to happen, so we made this rule, and if you only ever used the boards in the way we ask you too you shouldn’t have an issue. They did not tackle why a person exposed from any other direction besides directly above him, get a bonus from the aforementioned? Also, there is nothing wrong with a lavender counter color or perhaps even pink! as long as they are in the pastel vain should look rather neutral. The whole rebuttal of the designers was, it works when taking together as a whole. Problem is, it is an edition to an already created system and is in addition to. That means if any addition s from outside that module “break” the game or cause headaches, its a failure in that sense. I was about to buy this and a TPP new module but I cannot see a reason for a stand-alone game that uses the ASL rule book. Forgotten Heroes would have been better served by its own new ASL system that launches the beginning of a more modern ASL for the time span succeeding the ww2 era. Better then nothing…perhaps.

Apologies for the Copious errors featured in the text above. No edit function 🙁

Thanks for this very insightful review of the module. I’ve come to the same conclusions as you – that the design team for this was just too insular and got no pushback on some of their battier ideas.

I started with really not much opinion on the CPVA (in the context of the game), but the more I’ve played the IPM rules and the CPVA rules generally the more they have annoyed me. We all agree there are things that ASL has done that maybe don’t make a ton of sense (like the US’s 6 base ML) but that we appreciate, or at least live with, in the name of flavor and heightening contrasts. But I think the thing I’ve always appreciated about ASL is that it (generally) doesn’t go about being vindictive – it gives national armies capabilities rather than disabilities. Armies which had really abysmal performance in the field, which include the USSR, Romania, Italy, even the US, don’t get punitive special rules that make them look like idiots. As you say, not even partisans. Having to play the CPVA with these crazy, really heavyweight IPM rules just feels painful and insulting. The weird thing is that not only does IPM seem like a poor design choice, they also just seem like bad rules: if you have a lengthy board edge you can exit from, as in Seoul Saving for example, you can really game the hell out of them. The rule about area fire for non-adjacent targets is particularly bizarre and we’ve almost always forgotten it, which might be why the CPVA has a pretty good win ratio around here.

I just think it’s sad because there was a real opportunity to do something interesting here, but this is the first module for ASL that I really felt went pretty far off the rails, and could have been much improved just by doing a lot less (just making the CPVA a slight variation on the Soviets; or if you really must use the Japanese, just slim the rules load *way* down). Especially after my Hakkaa Paalle! experience – I went into that one with real skepticism but came out fairly impressed with the work they had done.